This is the second part of my review of Brian Zahnd’s book Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God. If you are interested, you can find the first part here; some of what I will refer to in this post can be found in the first part.

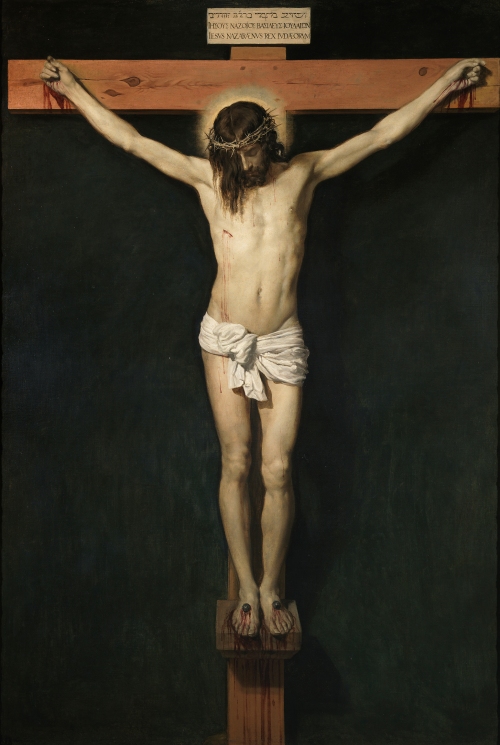

After focusing on the meaning of divine wrath and the nature of Christ as the most important word (message) of God to humanity, Zahnd shifts to consider the meaning of Christ’s death on the cross in two chapters, respectively titled “The Crucified God” and “Who Killed Jesus.” His argument spans around 35 pages, and so I obviously will not be able to touch on every aspect of his argument, but I will focus on what I feel are the main points (and again, I encourage anyone reading this to pick up Zahnd’s book for yourself).

At the most basic level Zahnd wants to challenge the idea that Christ’s death on the cross was a result of God’s need for an innocent sacrificial victim in order to forgive. For Zahnd, “the cross is not a picture of payment; the cross is a picture of forgiveness” (86); and is “not where God find a whipping boy to vent his rage upon…” (86). On the cross, “Jesus sacrificed himself to the love of God manifest in forgiveness, not to the wrath of God for the satisfaction of vengeance” (87). The cross should not be understood as an economic model where “God had to gain the necessary capital to forgive sins through the vicious murder of his Son” (101, 102), but rather as the place where God was “lynched in the name of religious orthodoxy and executed in the name of imperial justice…” (86).

Zahnd is reacting against a particular was of understanding Jesus’ death on the cross that, at it’s most primitive and simplistic, pits Jesus against his father, his torturous death saving us from God’s anger. In Zahnd’s view this understanding is not only incorrect but actually presents us with a warped and monstrous view of God as one who is either so beholden to justice, or so focused on vengeance and sacrifice, that he demands the death of an innocent (in an incredibly graphic and horrendous way) in order to forgive.

So who killed Jesus? According to Zahnd, not God, but us, our sinful system of evil, scapegoating, ritual violence, envy, and fear. All of these things reached a crescendo at the death of Christ, with the military, political, economic, and religious systems cooperating to put to death the son of God.

Before I address some of Zahnd’s arguments more in depth I want to start with a qualifier. The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus is such a mystery that we will never come to the end of it, never arrive at a point where we understand it fully. I believe that there are many ways of seeing these events, and that each view can stress a different aspect of what occurred during that event. Therefore, while there are undoubtedly understandings of the death of Christ that are simply wrong (ie: believing that Jesus “lost” his divinity before he was crucified, and so was just a man when he died), most theories or explanations of the meaning of Christ’s death are simply different emphases. I believe that is what Zahnd is doing here; I think he seeks to challenge a view of Christ’s death that puts an unhealthy stress on “payback,” on that portrays God as a bloodthirsty deity who must be placated with blood, a god who demands a ritual sacrifice. I also think he seeks to emphasize just how broken many of our systems (political, economic, religious) are, how they have so often caused violence, destruction, and bloodshed, and how they need to be redeemed and transformed by the forgiveness and love of God, a love and forgiveness that was revealed in the cross even as the cross was the ultimate expression of the evil of our systems.

My disagreement with Zahnd is that in his effort to challenge and correct a warped view of God as One who demands the brutal murder of an innocent person in order to bring about forgiveness, he ignores God’s righteous judgment of and opposition to sin. He wants to absolve God of killing Jesus, and yet, ironically, this has the effect of lessening the immensity of the grace and love shown by God through the cross of Christ. Zahnd’s teaching also, I think, fails to take adequate account of just how enslaved humanity is to sin, and what lengths God had to go to in order to free us from that enslavement. God did kill Christ, but this doesn’t make God a monster.

To see how this could be true we need to understand Scripture’s consistent teaching on the connection between sin and death. It starts with the story of Adam and Eve, who are explicitly warned by God that disobedience will result in their death (Genesis 2:15-17), continues in the story of God’s people, Israel, who are warned that disobedience and rebellion against God will lead to their death and destruction (Deut. 30:15-18), and even can be found in Paul’s statement that the wages of sin is death (Rom. 6:23). Sin equals death. We can question why this is so (and I personally like the explanation I found in a Donald Miller book, that God is life and the source of all life and to choose sin, which is the opposite of God, is to choose “not life”), but I don’t think we can ignore that it is true. We all sin, we are all trapped by the power of sin, and we all experience death in the myriad ways it plays itself out in our lives.

But what happens if God steps into the experience of being human, as the gospels assert that he did? What if God became one of us? What if God saw that humanity was enslaved by sin and could not free itself, and that this enslavement meant humanity could not be what it was created to be? What if God, having chosen a specific group of people to be his people, to reveal his light to the whole earth in order to bring them back to himself, saw that sin had enslaved even these people, his chosen people, and that they couldn’t be who he had called and created them to be? What if God saw all of this and decided to rescue us, and that he would do this would by becoming one of us, in order to do, and to be, what we were incapable of doing and being? What if Jesus identified so closely with us that he actually shared in our brokenness and sinfulness, even though he himself committed no sin?

This is what the New Testament says Jesus did. It says that he who knew no sin became sin for us (2 Cor. 5:21). It says that Jesus was willing to be counted among the transgressors (Luke 22:36-37). Jesus came to us, shared in what it meant to be us, and that included putting himself under the sentence of death that we are all under because of our sin, even as he lived the life of perfect obedience to and love for God the Father that all of us were created for and yet have failed to do.

This is what happens at the cross. Jesus’ life of obedience, and Jesus’ sharing in the totality of the human experience, come to fulfillment. He goes to the cross because he is unwaveringly obedient to his Father, and because this obedience is always something that must be resisted and destroyed by all of the powers and systems that have set themselves up in opposition to God. But he also goes to the cross because he has chosen to totally share in humanity’s experience, and that includes its sinful opposition to God, and the consequences of that opposition, God’s righteous judgment.

And so, we kill Jesus, and God kills Jesus. We kill Jesus because he is something we cannot control, because he is light and we loved darkness (John 3:19). God kills Jesus because sin is a rejection of God, who is life, and once you reject life the only option is death. He kills Jesus because we chose sin, and Jesus chose us, chose to come and identify with us to such a degree that he put himself under the power of sin and death, and under the righteous judgment of God against that sin.

This does not make God a monster; it reveals him as beautiful. Christ comes to be who we could not be, and in his death and resurrection overcomes our sin and recreates us, drawing us once again into the life and goodness of God even as he experiences in his own body the consequences of our rebellion. God reveals his righteousness in judgment against sin on the cross. It is ugly, not because there is something ugly about God’s judgment of sin, but because sin and all of its consequences, particularly death, is ugly. But in the cross we also see that God’s righteousness is not just judgment but mercy.

“When humanity fails to take up the creature’s side of the covenant, the righteousness that condemns is also the love that restores by surmounting even the obstacle of human disobedience and lawful subjection to death, to take up the human side on humanity’s behalf” (Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite, 368).

Once again, in wrath, God remembers mercy, and it is mercy, not wrath, that triumphs. Jesus doesn’t oppose God or placate God; Jesus is God, given to a creation who has rejected him so that even in this rejection they might find the gift of God’s mercy given again.

Towards the end of the chapter on who killed Jesus, Zahnd states what he believes to be the purpose of the cross. As with most Christians, Zahnd believes that the cross is the revelation of God’s love and forgiveness. But in seeking to absolve God of “killing Jesus” he reinterprets the crucifixion from the place where God fully judged sin, sin that was in some mysterious way taken on by Christ, to the place where we understand our “violent system of blame and ritual killing (to be) so evil that it is capable of the murder of God…(and so) we can repent of it, be forgiven for it, and be freed from it. This is how the cross saves the world” (114).

But that’s not how the cross saves the world. We didn’t need the cross to see how evil our systems are, we have thousands of years of history for that, and it’s clear that it doesn’t make a difference because we are enslaved to those systems. We need re-creation. We need righteousness, a righteousness that both opposes sin and reaches out in mercy, righteousness that judges and heals. We need God, Christ crucified, descending to us in our death to share in it and yet overcome it, raising us up in the power of his resurrection to be what we were always meant to be.

Pingback: Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God, Part 3: Hell and How to Get There | aphasiachronicles